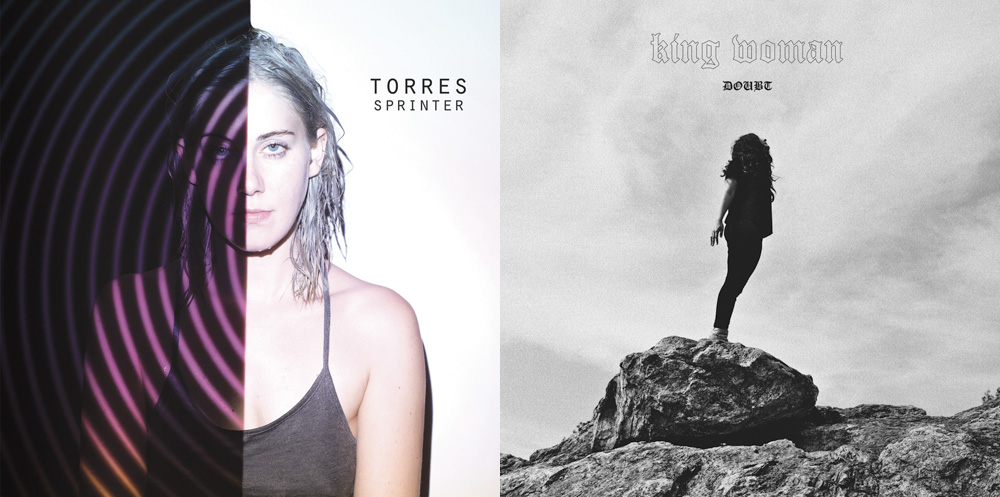

Songs of lost faith: Torres / King Woman

I’m not a religious person, but when I try to tell my kids why they really can’t bash each other’s heads in, why they should avoid the pull of materialism, or why evil and tragedy seem to flourish with no end in sight, I see why my own parents tried to raise me in faith. Religion offers attractive foundations that parents with their noses to the grindstone can lean upon when raising children: a vision of justice that transcends the visible world; a moral code that prescribes sanctions and cultivates consent among its adherents; a means for connection to kin and community; a basis for generational continuity within a vaguely defined, often unexplained ‘society.’ The seed of religion is buried deep within the family, literally and historically, which makes the betrayal of faith a powerful, often explosive source of emotional expression and artistic inspiration, as two new albums demonstrate.

Mackenzie Scott, an alt-rock musician who records as Torres, alludes to scenarios of profanation, recrimination, and exile at the hands of church and congregation on her forthcoming album Sprinter. Although solicitations to Jesus and identifications as a Baptist recur in her lyrics, these songs’ narrators can’t find the innocent security that childhood faith once offered. These themes can be tricky material to pull off, never mind the fact that listeners don’t all share her religious background. The first-person revelations and sense of woundedness that permeate the album are notoriously difficult for young musicians to wield skillfully; the traps of mawkishness and self-absorption especially await songwriters working in styles deemed “confessional,” to cite the critic’s term (that in fact may very well be unfairly stacked against women musicians).

Torres is able to walk this fine line, first, thanks to the production work of Rob Ellis, the long-time collaborator of PJ Harvey who heightens the visceral impact in these recordings, as heard on the wrathful “Strange Hellos.” This forceful alt-rock is at the same time cut with moments of beauty that add unexpected nuance, such as the way the chorus on Sprinter‘s title track points the song to its unsettling, eerie coda. Second, Mackenzie Scott’s voice — a dry, plain soprano that keeps its distance from listeners even in its prettiest passages — does a lot of the work of avoiding the traps of ungainly introspection and sentimentalism. When elsewhere on the album she sings forlornly, “There’s nothing in this world that I wouldn’t do/To show you that I’ve got the sadness too,” Torres conveys the ultimate tragedy of religious betrayal in a form that even the most secular listener might identify with.

By contrast, King Woman relates the experience of lost faith through a compelling and thickly atmospheric music. A four-piece group led by vocalist Kristina Esfandiari, King Woman fuse several underground styles known for their overwhelming ambience: the sinister crawl of doom metal, the hallucinatory densities of shoegaze, the lo-fi terror of black metal. The music on their EP Doubt almost totally drowns out Esfandiari’s lyrics, turning her breathy vocals into more of a lead melodic instrument. Still, the sentiments on opening track “Wrong,” which reference her background in a charismatic Pentacostal church, are worth note:

In my childhood

In my lonely world

In my troubled heart

I have seen something

I know it’s wrong

Laying on of hands

Demonize a man

Fill this place with fear

There’s no great spirit here

King Woman is obviously a very different entity than Torres, and I suspect much of their respective audiences would have little interest in the other’s music. Their commonality lies not only in their themes of lost faith but also the fact that they’re fronted by women; the former requires the artists to universalize their experience, while the latter puts forth its own, unfortunately gendered challenges. In the case of King Woman, the long tradition of heavy metal that they draw upon can be caricatured as dudes shrieking/growling lyrics that reject Christianity; Satan offers the familiar symbol (by now, a cliché) with which to project this viewpoint onto an external storyline. King Woman may or may not be a metal group, but it’s fascinating how they turn inside out the profane transcendance sought by many metal groups, particularly its “blackened” practitioners. The burden of religious negation lies on the shoulders of Esfandiari’s narrators, not Satan, which makes the artistic feat this group achieves all the more remarkable.

Torres’ Sprinter comes out May 4 on Partisan Records.

King Woman’s Doubt is out now on Flenser Records.