What the whole world wants: Game Theory

Indie-pop progenitors Game Theory were born either too late or too early. When they came to college radio’s notice in 1985, the northern California band sounded a little passé, like a new wave unit of the power-pop variety, brandishing undistorted guitars, blurts of synth melody, and male-female harmonies. American indie groups of the time generally washed a guitar-driven attack over listeners, with often brute, masculine force; by contrast, Game Theory required a bit of effort to adjust to frontman Scott Miller’s high-pitched voice (his self-styled “miserable whine”) and appreciate the sophistication, wordplay, and emotional heft of his songs. Since then, those songs have endured to burnish the legacy of Miller (who died in 2013) and Game Theory, who are now celebrated for some of the 1980s’ most virtuosic popcraft.

Omnivore Recordings has been releasing expanded versions of Game Theory’s catalogue over the last few years, and with the recent reissue of Game Theory’s final album, listeners today can rediscover one of the most astonishing runs of albums in alternative rock: the four albums Game Theory made in 1985-88 with producer Mitch Easter. Better known for the murky jangle he coaxed out of R.E.M. and his own group Lets Active, Easter surprised listeners with his embrace and enhancement of Game Theory’s bright sound, playing low-budget George Martin to Miller’s Brian Wilson. Their collaboration and the evolution of Game Theory into a stunning, assured unit have withstood the test of time, as these four releases document.

Real Nighttime (1985)

Though Game Theory had self-released previous records, Real Nighttime feels like a five-star debut album. Lead track “24” illustrates the band’s MO: guitars and keyboards weave catchy figures into each other; a frisky rhythm section accents and syncopates; and referential elements (e.g., the title’s shifting meaning over the choruses, the musical quotation from “Stairway to Heaven” at the fade-out) nuance an otherwise earnest expression of Gen X discomfort… all in under three minutes! Miller’s unerring instinct for the hook and Easter’s lean production provide necessary balance to sometimes dense compositions loaded with complex intros and codas, pre-choruses and choruses, bridges and alternate bridges. Remarkably, even through a petulant sneer (as on “Friend of the Family” — those syn-drums!), Real Nighttime sounds delightfully breezy and poppy.

The Big Shot Chronicles (1986)

With the bar set for Miller’s compositional ambitions, The Big Shot Chronicles advances the Game Theory oeuvre, first, by the sonic crispness that Easter delivers — a hallmark of their recordings from here on out. Second, while Miller continues to draw from the power pop well, with occasional diminishing returns, he expands the scope of his songwriting in two essential Game Theory tracks, the gorgeous folk koan “Regenisraen” and the woozy psychedelia of “Like A Girl Jesus.” Meanwhile, I dare you to find a more perfect pop song than “Erica’s Word.”

Lolita Nation (1987)

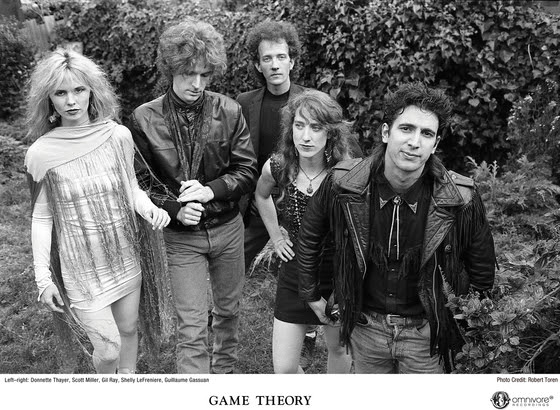

Perhaps restless with the lack of commercial traction Game Theory had received to date, Miller just shrugged and steered the band in a perverse direction on Lolita Nation. Cherished by some fans as the band’s White Album, the album sprawls with musical snippets, Easter’s editing tricks, and songs penned by other members, while Miller’s lyrics turn increasingly mocking and cynical (e.g., “Nothing New”). Still, the album is muscular and confident, in large part due to Miller assembling the classic five-member line-up (see photo above). Some fans may challenge this, but these left-field components add valuable edge to a band that had long established it could create ‘merely’ perfect, personal pop. The single “The Real Sheila” — the last time Game Theory would appear on MTV’s 120 Minutes — juggles all these elements with panache.

2 Steps From The Middle Ages (1988)

At the time of Game Theory’s final album, college radio was shifting toward grunge and industrial in North America and shoegaze and “Madchester” dance pop in the UK — all relatively tuneless in comparison to the indie pop the band plied. 2 Steps From The Middle Ages fell off the radar so quickly upon release. The tragedy is it shows Game Theory and Easter getting serious about forging an accessible sound that consolidates their strengths and retains their musical integrity. Tracks like the strutting “What The Whole World Wants” flash considerable teeth, the band meshing their disparate elements effortlessly, while “Amelia Have You Lost” (another entry in the subset of Game Theory songs with women’s names in the title) is a plaintive ballad that reveals the wear on the romantic heart Miller had exposed for so many years. Everyone’s got their preferences, but I’d say 2 Steps From The Middle Ages is in many ways the quintessential Game Theory album.

There would be another shuffling of band members (to include Michael Quercio, of the like-minded Three O’Clock) and a few new recorded tracks, but Game Theory effectively ended when the 80s did. In the new decade, Miller launched the Loud Family, another sadly overlooked “critic’s fave” whose first album also featured Mitch Easter as producer. (Here’s a plea to Ominvore Recordings to reissue that band’s albums next.) Miller’s legacy can be easily Googled, and it should, but by all means head first to these crucial albums. You can find these reissues including bonus tracks on streaming services, but forking over cash gets you the fantastic liner notes that, when read together, comprise the book on Game Theory that we all want.